Winsconsin

One of the country's largest concentrations of Walloon-speaking Belgians is found in northeastern Wisconsin, resulting in a unique cultural and social flavor.

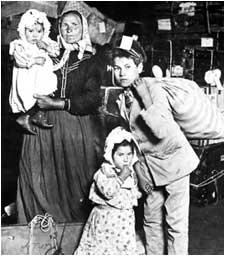

The largest wave of Belgian immigration to Wisconsin occurred in the mid-1850s,following the lure of farmland that could be purchased from 50 cents to $1.25 an acre.

Here they cleared fields, felled trees, and built rude log shelters to house their families.

Writing back home of their satisfaction with their new lives, they soon were joined by thousands of their fellow countrymen.

While the 1850 U.S. Census lists only 45 persons of Belgian nativity in the state, by 1860 the number had increased to 4,647.

The 1890 U.S. census also shows that 81% of Belgians in the state lived in the northeastern counties of Brown, Kewaunee, and Door.

The Belgian immigration into northeastern Wisconsin came to an abrupt halt in about 1858, when word reached the homeland of the physical and economic hardships and the cholera epidemic sweeping the settlement.

The first Belgian settlers made a living making shingles and farming small plots of land.

This changed in the fall of 1871 when a major fire (the same that devastated Peshtigo on the same day as the great Chicago fire) swept through Belgian settlements and virtually destroyed the shingle industry.

After the fire, farming became the major industry, but because the farms were small, income was often supplemented in the winter by commercial fishing.

Some men also migrated to the lumber camps in northern Wisconsin at Thanksgiving time and returned home in April; during this period, the women and children assumed responsibility for feeding and caring for the livestock.

Barriers of language and rural poverty tended to isolate and insulate the Belgians from their neighbors.

While Belgians from both the Flemish and Walloon provinces have settled in Northeastern Wisconsin, the Walloons have remained a more homogeneous, readily identifiable ethnic group.

The Belgians in this area generally believe, erroneously, that Walloon is only an oral (not written) language, and because it has been passed down orally in this part of the country, it may be regarded as a folk language.

Walloon is a French patois. French was used in church records, correspondence, mourning cards, etc.

Today, many Belgian descendents still reside in the 35 square mile area settled by their ancestors. In many cases, farms have been in the same family for over 100 years. Fourth and fifth generation Belgians still speak together in Walloon, and continue such customs as the celebration of Kermis (a harvest festival held in early fall) and the erection of a "maypole" in the yard of a winning political candidate. The presence of small wayside religious shrines also illustrates Belgian influence.

Source: Univerisity of Wisnconsin - Belgian-American Research Collection

|